Cyntia Verduzco eats lunch at East Los Angeles College before her chemistry class. (Fernando Hurtado/JOUR 309)

Cyntia Verduzco eats lunch at East Los Angeles College before her chemistry class. (Fernando Hurtado/JOUR 309)

At East Los Angeles College (ELAC), stress runs high for at least 172 students.

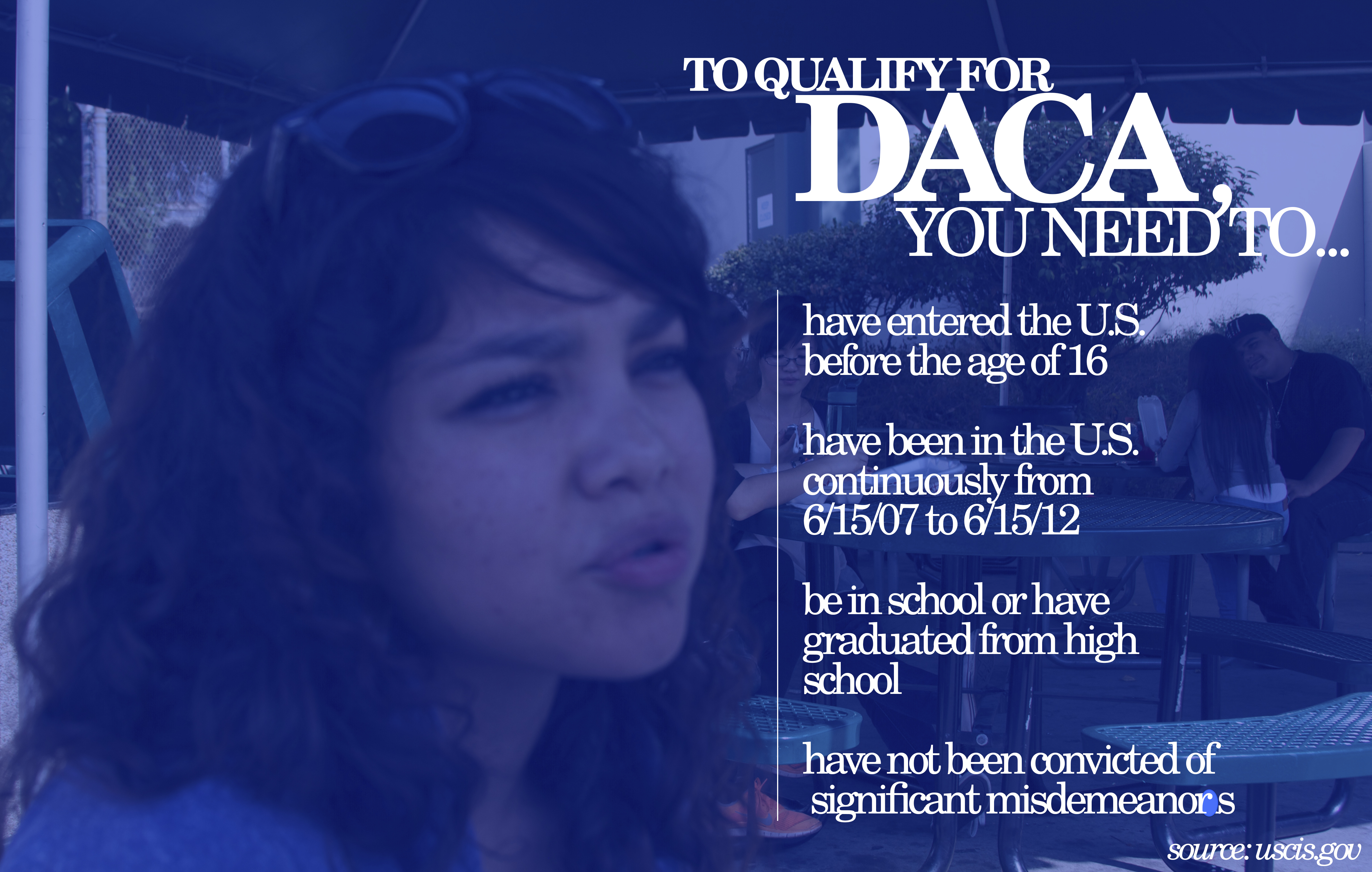

For these students, October means they just reapplied for Deferred Action Against Childhood Arrivals (DACA), an executive order passed in 2012 that defers the "removal of certain eligible undocumented youths" and allows them to work and study legally for two years at a time.

For Cyntia Verduzco, 25, this month could be a defining moment in her future. If her DACA is renewed, she will be able to keep studying for another two years and complete her bachelor's in nursing at California State University, Long Beach, like she's always wanted. But if it's not approved, she could have to move to Guadalajara, Jalisco, the Mexican town where she spent the first nine months of her life.

"That would suck," said Verduzco while on a break between classes. "That would just completely ruin my future and everything because, what am I going to do now?"

Because DACA is an executive order, it means it could be overturned at anytime by Congress or a change of power. Verduzco says she's learned to live with the uncertainty.

"I don't get it," Verduzco says referring to her 22-year-old brother who was born in Los Angeles. "He has everything he needs to make his dreams come true, but he decided to drop out. I don't have anything, and I'm the one who can't chase them even though I want to."

"In any case," said Verduzco, "this is the most certain my life has ever been. I've been used to living in the shadows and hiding from airports, borders and police in my neighborhood. It's nice to finally have an identity and nothing to hide."

Verduzco says this as she caresses the top edge of her California driver's license with her thumb from left to right, and then right to left, repeatedly. She was able to get this when her approved DACA application granted her a Social Security number. Verduzco also got something she had never had in her 25 years alive: a job.

"Disneyland is my first job," she said. "I love it. Everyone's so nice."

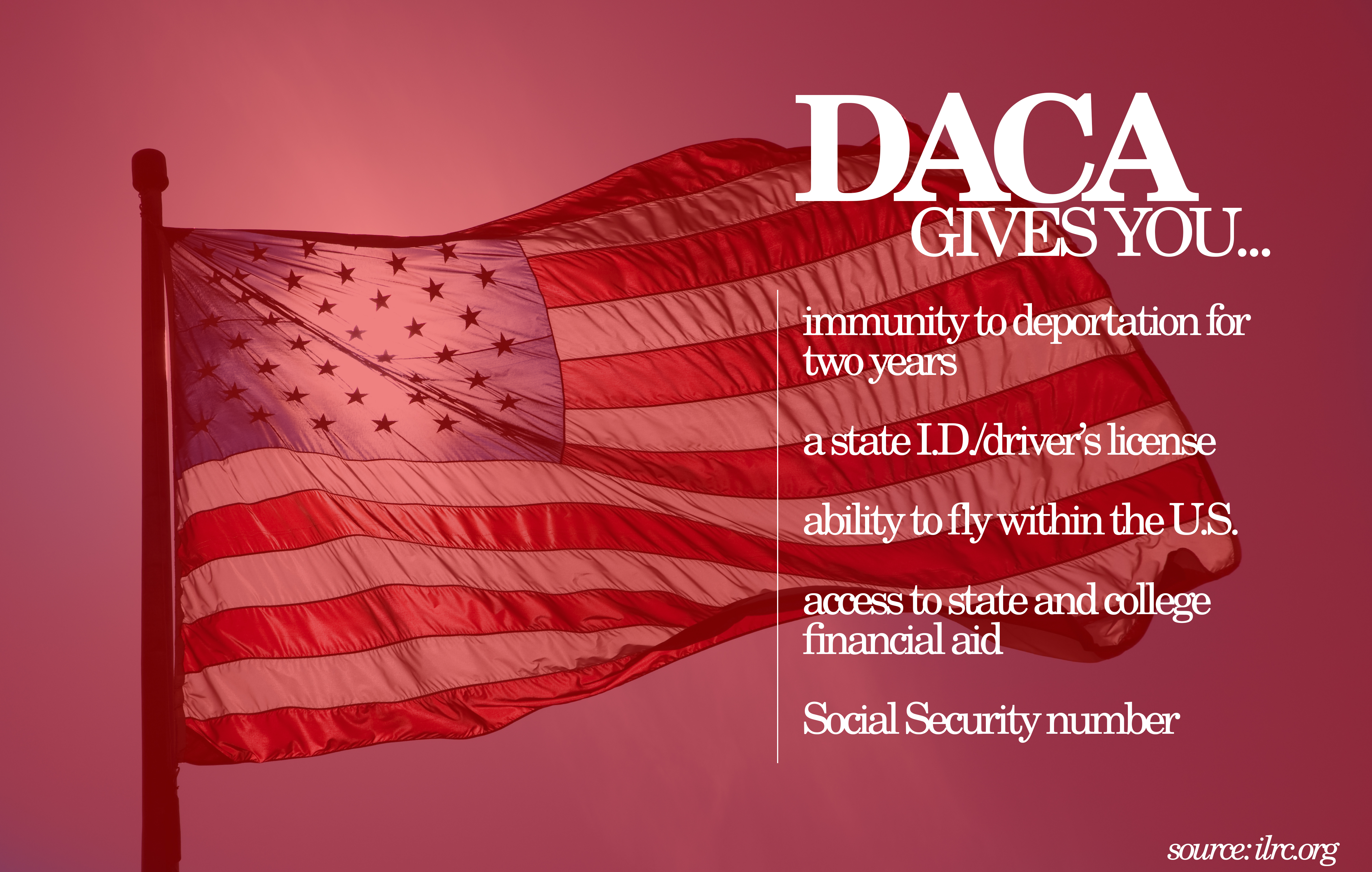

The benefits of DACA are numerous, eligible applicants get a Social Security number, access to financial aid and scholarships at ELAC, a driver's license, an education, and if they want, a job. But these benefits come at a price.

Attorney Violeta Delgado, who serves the East L.A. community, said a lot of her DACA clients don't apply because of the high filing fee of $465.

Verduzco said she spent $900 on her first application in 2012--$465 for the application and close to $500 for services from a notary. This year, she only had to pay $200 for the notary public's services because it was a renewal and not a first-time application, which is easier to process, according to Maria Velazquez, an intake screener at the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles.

Most of the time, however, what holds people back from applying are the age requirements, not the price, said Attorney Violeta Delgado.

"I see a lot of people who don't apply because they meet every other requirement but aged out because they were over 31 on June 15, 2012, when the [policy] was announced," said Delgado.

That's not the only requirement disqualifying some "childhood arrivals." In addition to having entered the United States before the age of 16, they must have had continuous residence from June 15, 2007 to June 15, 2012. Qualified applicants must also either be in school, graduated from high school or obtained a G.E.D or be an honorably discharged veteran, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

While those who do qualify for DACA and choose to enroll in public universities don't qualify for federal aid under the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), they can qualify for state and college financial aid using that same application. That's how Verduzco is paying for ELAC.

"I only have to pay my books, which is really nice," said Verduzco.

With financial aid now publicly at her disposition, Verduzco said she's excited for her future.

"I heard that once you renew [DACA] for third time, you automatically get citizenship, but that's just a rumor right now," said Verduzco.

"That's not true," said Delgado. "The original DREAM Act did provide an avenue to residency, but DACA is just work permits."

It's neither as good nor as bad as it sounds, argues Delgado. "For some reason, rumor got out among the Latino community that this was a trap to get their addresses and then deport them. That's also not true."

As for Verduzco, she'll know by the end of October if it's worth it to pay extra for the tutoring she needs to pass her chemistry class or leave those dreams behind and pay for a bus ticket to a "stable identity" in Mexico, as she calls it.